1. Introduction

Today’s wicked issues, such as climate change, force us to learn about them and their mitigation methods (Lehtonen et al., 2018). Such complex learning processes call for ludonarrative media, such as digital role-playing games (Mao et al., 2022). Guided by game science (Klabbers, 2018), these media can reach their full educational potential by encompassing gaming, i.e., the “small-g game,” and its various surrounding activities, such as pre- and post-game discussions, to realize the “Big-G game” (Gee, 2024).

However, there are urgent gaps regarding designing ludonarrative media for game-based learning (GBL). Firstly, their design necessitates transdisciplinary teamwork, which frequently struggles with conceptual robustness due to the divergence of theories and methods (Boon et al., 2014). Complicating the matter, a conceptually robust design may not reflect the end product as a technological artifact (Jongeling et al., 2022), thus lacking scientific precision for its validation and verification (V&V) and technical realizability with which to turn it into a usable system. There is also a fourth problem of practical adaptability concerning design evolution that maintains existing functionality (Goel & Ratneshwer, 2023).

Current methods, such as the Learning Mechanics-Game Mechanics model (Arnab et al., 2015) and the RAGE framework (Westera et al., 2019), solve these problems only partially. Yet, it is imperative to address the four problems equally. Firstly, they correspond with the fundamentals of game science: its philosophical, scientific, and applicative aspects (Klabbers, 2018). Secondly, their joint contribution to the product’s complexity and, in turn, costs scales exponentially (Chapman et al., 2001; Ogheneovo, 2014). Being the pinnacle of learning technology, Big-G GBL is thus most susceptible to this cost explosion, barring stakeholders with limited resources, primarily those from developing countries, from utilizing it to solve Sustainable Development Goals 4 (quality education) and 10 (reduced inequality).

My ludonarrative universe model can potentially solve the four problems. I will discuss the model, its strengths, and my plan for doctoral research on the model.

2. The Ludonarrative Universe Model

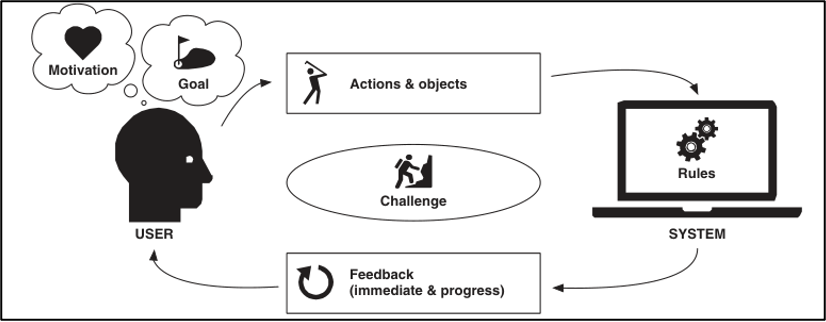

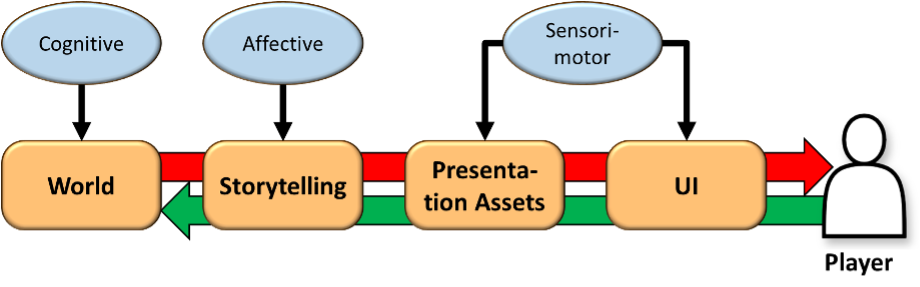

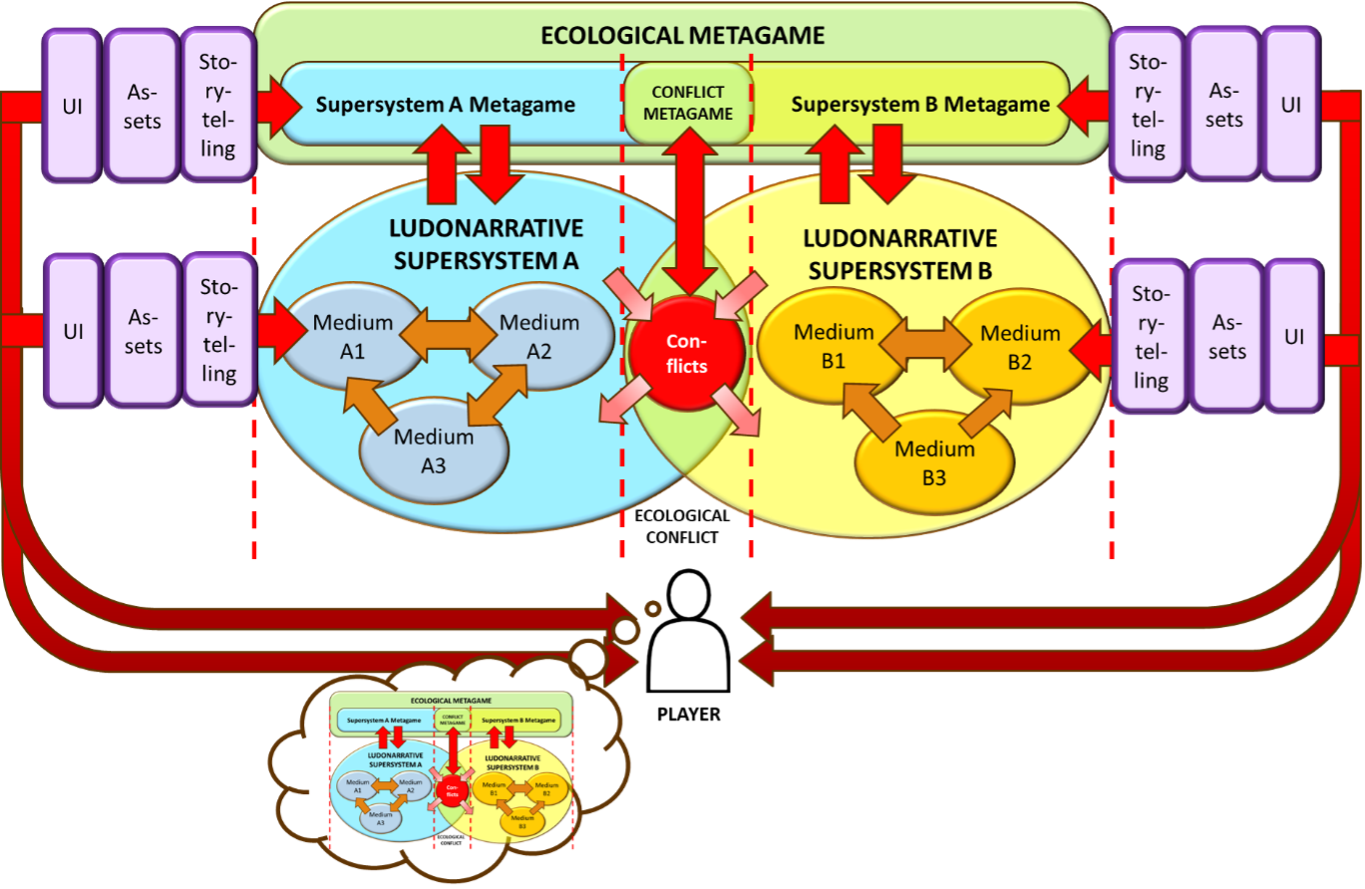

Following the established Game Loop theory (Deterding, 2015) as seen in Figure 1, the model consists of, first and foremost, ludonarrative media as dynamical systems. The media’s organization will then occupy four dimensions. Firstly, similar to nested games (Distefano & D’Alessandro, 2021), a set of ludonarrative media can jointly operate as a supersystem, letting the player explore a complex subject’s hierarchical intricacy. Secondly, like megagames (Johansson et al., 2023), any ludonarrative medium can have ecological counterparts with which it conflicts or competes, representing the tension between the subject’s elements, including its multiple interpretations. Thirdly, the player can manage the media and their conflicts through layers of metagaming (Klabbers, 2018). While these three dimensions already accommodate in-game and out-of-game activities, the last one rounds the technology out by letting each ludonarrative medium optimize player experience through cognitive, affective, and sensorimotor domain-related layers: (1) a world layer that simplifies the learning subject without incorrectly representing it, (2) a storytelling layer that engagingly and empathetically delivers the world, and (3) an asset and UI layer that sensorily manifests the storytelling and lets the player control it (Atmaja & Sugiarto, 2022). Figure 2 illustrates this experiential arrangement.

Figure 3 illustrates a 4D ludonarrative universe. Together, its four ludonarrative dimensions may realize a robust, precise, realizable, and adaptable Big-G GBL due to being:

1) Conceptually comprehensive: According to my cross-disciplinary literature review (Atmaja et al., 2024), the four dimensions quite possibly encompass the entire conceptual space of ludonarrative media, their finer-grained elements, and their discipline- or industry-specific use cases.

2) Fundamentally systemic: This quality allows the scientifically precise V&V of the universe from the beginning of its design process, aligning with the state of the art in model-based software engineering (Cederbladh et al., 2024).

3) Scale-invariant: The universe’s four dimensions serve as a structure that always remains regardless of the universe’s scale, thus cutting across design phases and levels of detail. This way, the currently active phase needs only to flesh out the preceding phase’s output without radically changing its structure, easing the universe’s realization.

4) Modular: Another common characteristic of systems is modularity, which balances cooperation with individual independence. For this reason, the ludonarrative universe may agilely adapt to a wide range of use cases due to exhibiting a “plug-and-play” quality, which eases removing existing elements and adding new ones.

3. Research Plan

My doctoral research will investigate the model’s potential through a case study of Big-G GBL on sustainability, whose interconnectedness warrants the four ludonarrative dimensions (Lehtonen et al., 2018). Specifically, my research will (1) verify the model’s four strengths, (2) identify ways to optimize the strengths, and (3) generalize the case study to other use cases of the model (Flyvbjerg, 2006).

The case study will consist of two phases, each adopting design science research (Peffers et al., 2007). Firstly, I will iteratively and gradually, one level of detail at a time, co-design and co-evaluate, with relevant stakeholders and experts, a 4D ludonarrative universe for Big-G GBL on personal sustainability. The universe’s expected constituents are games with interconnected, i.e., hierarchical and ecological, mechanics and narratives accompanied by analytics and rule management modules for metagaming and meta-metagaming (Boluk & LeMieux, 2017). The second phase afterward expands the universe for the larger issue of community sustainability.

Simultaneously, I will use a domain-specific language (DSL) to formally specify the universe’s design (Cederbladh et al., 2024). A V&V module will then execute the specification to check for its violations of gameplay and learning requirements. Furthermore, to support the entire co-design process, the DSL and V&V module will accommodate multiple levels of design detail.

4. Conclusion

I have discussed the ludonarrative universe model and my plan for doctoral research on its use for designing robust, precise, realizable, and adaptable Big-G GBL. Through a case study and design science research, I intend to realize the model’s potential to make Big-G GBL affordable for all.

References

- Arnab, S., Lim, T., Carvalho, M. B., Bellotti, F., De Freitas, S., Louchart, S., Suttie, N., Berta, R., & De Gloria, A. (2015). Mapping learning and game mechanics for serious games analysis. British Journal of Educational Technology, 46(2), 391–411. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12113

- Atmaja, P. W., & Sugiarto. (2022). When Information, Narrative, and Interactivity Join Forces: Designing and Co-designing Interactive Digital Narratives for Complex Issues. In M. Vosmeer & L. Holloway-Attaway (Eds.), Interactive Storytelling. ICIDS 2022. LNCS, vol. 13762 (pp. 329–351). Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-22298-6_20

- Atmaja, P. W., Sugiarto, Maulana, H., Kartika, D. S. Y., & Via, Y. V. (2024). The Many Ludonarrative Professions of a Ludified and Narratified Future Society. In N. Koenig, N. Denk, A. Pfeiffer, T. Wernbacher, & S. Wimmer (Eds.), Money | Games | Economies (pp. 255–279). University of Krems Press. https://doi.org/10.48341/29jx-be71

- Boluk, S., & LeMieux, P. (2017). Metagaming: Playing, Competing, Spectating, Cheating, Trading, Making, and Breaking Videogames. University of Minnesota Press. https://doi.org/10.5749/j.ctt1n2ttjx

- Boon, W. P. C., Chappin, M. M. H., & Perenboom, J. (2014). Balancing divergence and convergence in transdisciplinary research teams. Environmental Science & Policy, 40, 57–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2014.04.005

- Cederbladh, J., Cicchetti, A., & Suryadevara, J. (2024). Early Validation and Verification of System Behaviour in Model-based Systems Engineering: A Systematic Literature Review. ACM Transactions on Software Engineering and Methodology, 33(3), 1–67. https://doi.org/10.1145/3631976

- Chapman, W. L., Rozenblit, J., & Bahill, A. T. (2001). System design is an NP‐complete problem. Systems Engineering, 4(3), 222–229. https://doi.org/10.1002/sys.1018

- Deterding, S. (2015). The lens of intrinsic skill atoms: A method for gameful design. Human-Computer Interaction, 30(3–4), 294–335. https://doi.org/10.1080/07370024.2014.993471

- Distefano, T., & D’Alessandro, S. (2021). A new two-nested-game approach: linking micro- and macro-scales in international environmental agreements. International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics, 21(3), 493–516. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10784-021-09526-7

- Flyvbjerg, B. (2006). Five Misunderstandings About Case-Study Research. Qualitative Inquiry, 12(2), 219–245. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800405284363

- Gee, J. P. (2024). Response to ‘Postdigital Videogames Literacies: Thinking With, Through, and Beyond James Gee’s Learning Principles’ (Bacalja et al. 2024). Postdigital Science and Education, 6(4), 1099–1102. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42438-024-00508-x

- Goel, S., & Ratneshwer. (2023). Non-disruptive change management modeling of SOA based systems. International Journal of System Assurance Engineering and Management, 14(S1), 455–471. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13198-023-01875-7

- Johansson, B., Berggren, P., & Leifler, O. (2023). Understanding the challenge of the energy crisis – tackling system complexity with megagaming. ECCE ’23: Proceedings of the European Conference on Cognitive Ergonomics 2023, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1145/3605655.3605689

- Jongeling, R., Ciccozzi, F., Cicchetti, A., & Carlson, J. (2022). From Informal Architecture Diagrams to Flexible Blended Models. In I. Gerostathopoulos, G. Lewis, T. Batista, & T. Bureš (Eds.), Software Architecture. ECSA 2022. LNCS, vol. 13444 (pp. 143–158). Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-16697-6_10

- Klabbers, J. H. G. (2018). On the Architecture of Game Science. Simulation & Gaming, 49(3), 207–245. https://doi.org/10.1177/1046878118762534

- Lehtonen, A., Salonen, A., Cantell, H., & Riuttanen, L. (2018). A pedagogy of interconnectedness for encountering climate change as a wicked sustainability problem. Journal of Cleaner Production, 199, 860–867. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.07.186

- Mao, W., Cui, Y., Chiu, M. M., & Lei, H. (2022). Effects of Game-Based Learning on Students’ Critical Thinking: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 59(8), 1682–1708. https://doi.org/10.1177/07356331211007098

- Ogheneovo, E. E. (2014). On the Relationship between Software Complexity and Maintenance Costs. Journal of Computer and Communications, 02(14), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.4236/jcc.2014.214001

- Peffers, K., Tuunanen, T., Rothenberger, M. A., & Chatterjee, S. (2007). A Design Science Research Methodology for Information Systems Research. Journal of Management Information Systems, 24(3), 45–77. https://doi.org/10.2753/MIS0742-1222240302

- Westera, W., Fernandez-Manjon, B., Prada, R., Star, K., Molinari, A., Heutelbeck, D., Hollins, P., Riestra, R., Stefanov, K., & Kluijfhout, E. (2019). The RAGE Software Portal: Toward a Serious Game Technologies Marketplace. In M. Gentile, M. Allegra, & H. Söbke (Eds.), Games and Learning Alliance. GALA 2018. LNCS, vol. 11385 (pp. 277–286). Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-11548-7_26